Edward Condon was a strong believer in international scientific collaboration. Having studied under such famed physicists as Max Born and Arnold Sommerfeld, Condon was able to make significant contributions to the field of quantum mechanics, particularly, to the development of radar. His openness to global cooperation did, however, raise some eyebrows in the atomic age. To celebrate his birthday, let’s unpack the life of Condon, his contributions to quantum mechanics, and his struggle to prove his loyalty amidst government scrutiny.

Embracing a Future in Physics

Condon was born on March 2, 1902, in Alamogordo, New Mexico. He worked as a journalist at the Oakland Inquirer before attaining his PhD in physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Thanks to a National Research Council fellowship, he was then able to study in Germany under Max Born (in Göttingen) and Arnold Sommerfeld (in Munich), theoretical physicists who were instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics.

Edward Condon as he appeared as the Director of the National Bureau of Standards. Photo credit: National Institute of Standards and Technology Digital Archives, Gaithersburg, MD 20899.

Presenting Papers, Patents, and Projects

Between 1928 and 1937, Condon primarily taught as an associate professor of physics at Princeton University. During this time he coauthored two books: Quantum Mechanics (1929) with Philip M. Morse, which was the first English-language text on this subject at the time, and the Theory of Atomic Spectra (1935) with G.H. Shortley.

After his stint at Princeton, Condon became the associate director of research at the Westinghouse Electric Company. Here, he headed research into microwave radar development and established research programs in nuclear physics, solid-state physics, and mass spectrometry. During the early years of World War II, Condon served as a consultant to the National Defense Research Committee and helped organize the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Radiation Laboratory.

The Nimatron

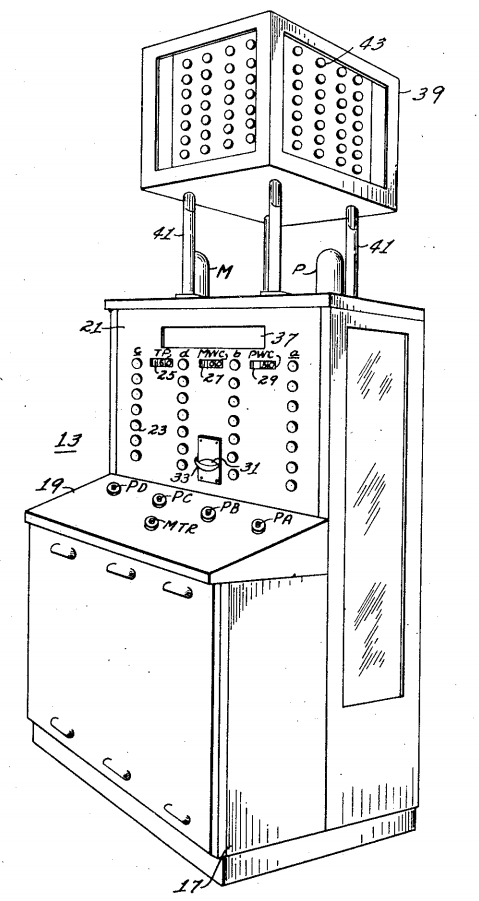

At the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair, Condon showcased his Nimatron machine as part of Westinghouse’s display. He later filed and received a patent for this nonprogrammable, digital computer that could be used to play the mathematical combinatorial game Nim. The machine could respond to players’ choices and even had delayed calculations to convince players that the machine was ‘thinking’ about its next move.

The image of the Nimatron from the patent. In general, the contents of United States patents are in the public domain.

While the game was a success with fairgoers, it was seen by Condon and Westinghouse as an entertainment device rather than as a technological advancement. Noting that, the Nimatron can be considered one of the first computing devices designed solely for gaming, beating out the Nimrod computer by just over a decade.

Battling for Atomic Energy Control

Condon was recruited to be the Assistant Director of the Manhattan Project in 1943. Six weeks later he resigned due to conflicts with the project’s military leader, General Leslie R. Groves, over strict security measures and living conditions. After that, he worked part-time as a consultant for the project while at the University of California, Berkeley. His focus was uranium separation, in particular, the separation of U-235 and U-238.

He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1944 and was one of the prominent American scientists invited to the 220th anniversary of the founding of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow in June 1945. General Groves believed that this trip would be a threat to national security. He argued that Condon had extensive information about the ongoing Manhattan Project, and the United States couldn’t risk anyone sharing information with the Soviet Union, inadvertently or otherwise. Condon’s passport was therefore revoked by the State Department and he was unable to attend.

Keeping the Peace

Condon knew the destructive capabilities of atomic weapons and believed that international collaboration and civilian control of atomic energy were the keys for avoiding nuclear war. To achieve the latter, Condon worked as science adviser to Senator Brien McMahon, the Chairman of the Senate Special Committee on Atomic Energy. McMahon helped build and pass the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, which created the United States Atomic Energy Commission (1946–1975). This commission took over control of atomic energy from the military, a measure that Condon thought would be crucial for peace.

For his work in fostering international scientific collaboration, Condon joined or associated with groups such as the American–Soviet Science Society and the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions. With tensions rising between the United States and the Soviet Union, these associations, alongside his aforementioned attempted trip to Moscow, brought government scrutiny and raised questions about Condon’s loyalty to the United States.

Scrutiny and Suspicion

The accusations of disloyalty began with Rep. J. Parnell Thomas, head of House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He openly questioned Condon’s loyalty in a pair of scathing articles published in the Washington Times-Herald, a newspaper based in Indiana. His fear and claims were that Condon would willingly give out atomic secrets to the scientists and officials of the Soviet Union. The Department of Commerce cleared Condon of disloyalty charges on February 24, 1948, but this would do little to alter the opinion of Rep. Thomas or the HUAC.

UFO Research, Retirement, and Legacy

Condon continued to work after the controversy and served as a professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis from 1956 to 1963 and then at the University of Colorado Boulder from 1963 until he retired in 1970. Still well respected in the academic community, Condon was asked by the U.S. Air Force to conduct a study of UFOs and explore whether they could be of extraterrestrial origins. The Condon report, the summarization of the multiyear study, concluded that UFOs have prosaic explanations and warranted no further investigation.

An image of the Condon crater with surroundings, taken by Lunar Orbiter 1. Photo credit: NASA/Lunar and Planetary Institute.

Condon’s impact can be found in the Franck—Condon principle, which describes the intensity of vibronic transitions, and the Slater—Condon rules, which express integrals over wavefunctions in computational chemistry. In 1976, Condon was honored with the naming of the Condon crater, a lunar crater, to recognize his interest in astronomy. However, his impact and legacy extend beyond this and Condon stands as a scientist ahead of his time, as someone who pushed for international scientific collaboration and cautioned the world against nuclear war.

Further Reading

Check out other interesting scientists and inventors on the COMSOL Blog:

- Niels Bohr, one of the most prominent physicists of the 20th century

- John von Neumann, a mathematician and polymath

- George Westinghouse, an inventor who helped shape how we use electricity in America and throughout the world

Comments (0)