You may not know Douglas Engelbart by name, but you probably use one of his inventions every day — the computer mouse. His vision of a connected, collaborative network of information paved the way for computers and the internet as we know it today. At a time when computers used punch cards for quantitative tasks, he envisioned a future of sharing information to solve complex human problems. In celebration of his birthday, let’s explore his innovations and lasting legacy.

The Man Behind the Mouse

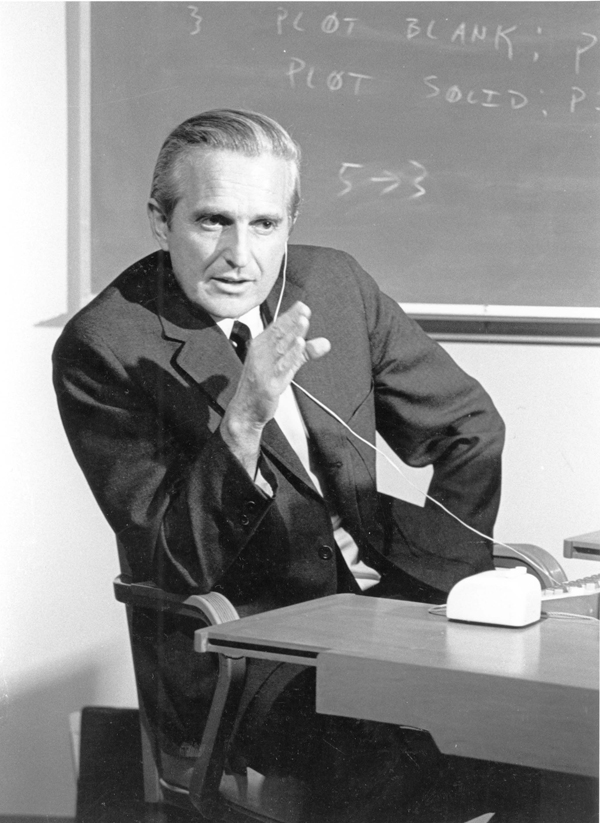

Douglas Engelbart was born on January 30, 1925, in Portland, Oregon, to Carl and Gladys Engelbart. His father passed away when he was nine years old, and he spent most of his childhood with his brother and sister living in the countryside outside of Portland. After graduating from high school in 1942, he enrolled in Oregon State University but left to serve in the United States Navy. He was stationed in the Philippines as a radio and radar technician. After serving for two years, he returned to Oregon State and received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1948.

A portrait of Douglas Engelbart taken in December 1968. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Original photograph in the collections of SRI International.

Engelbart’s first job was in wind tunnel maintenance at the Ames Research Center. During this time, he met his wife, Ballard Fish, who was an occupational therapist. After a couple of years working for Ames, Engelbart studied electrical engineering with a specialty in computers at the University of California, Berkeley, earning a master’s degree in 1953 and a PhD in 1955.

Inspired to return to school and study computers after realizing he had achieved his two life goals of getting married and having a steady job, Engelbart contemplated how to best find meaning in life. He determined that focusing his career on making the world a better place was the way to go. He believed that efforts to “harness the collective human intellect of all people to contribute to effective solutions” was the best way to improve the world, and he felt that computers had the power to dramatically improve this capability. Another significant influence on Engelbart leading up to his inventions was an article called “As We May Think” by Vannevar Bush, which he read while stationed in the Philippines. The article’s message is a call to action to make knowledge widely available as a national peacetime challenge. These two sources of inspiration, combined with his experience as a radar technician and engineering degree, launched him into the world of research.

Reimagining the Computer

In 1957, Engelbart took a position at the Stanford Research Institute. There, he worked on a number of subjects and eventually received funding from the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) to establish his own lab: the Augmentation Research Center (ARC).

During Engelbart’s time at the ARC lab, the current method for computer operation involved multiple pointing devices that selected items on the screen in a cumbersome way. He believed he could create a more efficient device and came up with the concept of using a small pair of wheels rolling over a tabletop. By having one wheel turn horizontally and the other vertically, the computer could accurately track their combined movements, resulting in a smoother cursor movement on the screen.

He and his team built what would become the first computer mouse prototype in 1961. It featured perpendicular wheels mounted inside a carved out wooden block and a button on top. They nicknamed it “mouse” because the cord sticking out reminded them of a mouse’s tail, and the name has stuck to this day. They tested a wide range of designs including a knee controller, joystick, and light pen, but ultimately decided to stick with a design very close to their original idea. SRI filed a patent on the mouse under the technical name of “x, y position indicator for a display system” and was awarded the patent in 1970.

Engelbart and SRI International’s first computer mouse prototype, photographed in September 2005. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Original photograph in the collections of SRI International.

Engelbart also shaped the modern-day computer with the vision he shared in a presentation on December 8, 1968. He introduced networked computing to a crowd of 1,000 engineers in San Francisco, in a presentation known today as “the mother of all demos”. He demonstrated how computers could be used for designing, editing, and collaborating using words. This was revolutionary at a time when computers were primarily used by programmers using punch tasks for quantitative tasks like inputting data, writing code, or calculating equations. He showcased typing on a keyboard with letters and numbers instead of using a punch card, making it more accessible to people who weren’t programmers. He introduced word processing, document sharing, version control, hyperlinks, the ability to backspace, and text and graphic integration at this demo. He had a vision of human-computer interaction, and he foresaw computers as we know them today. He saw them as a tool for designing, manipulating, collaborating, and sharing information.

Engelbart also foreshadowed the internet in this demo and sought to bring his vision of a connected network to life. He hired several women to go out to other institutions to build “networked improvement communities” because he had three daughters and believed that women would be ideal for building new cultures. This decision was quite unpopular, as investors wanted his lab to focus on optimizing personal productivity on the computer rather than establishing a network of thinkers.

As his vision diverged from the popular path, the ARC lab lost its funding, and the mouse, along with many of its engineers, moved to the nearby Xerox PARC lab led by Alan Kay. In 1979, Steve Jobs and other Apple executives toured the Xerox PARC lab and eventually purchased the rights to the mouse for $40,000. However, it wasn’t commercially available until Apple released the Macintosh computer in 1984.

In the late 1970s, SRI turned the ARC lab over to new management, who then hired Engelbart as a senior scientist and rebranded some of his software. Around that time, Engelbart’s house burned down, and he continued to face marginalization. In 1986, he decided to retire in order to focus on his own work independently. He, along with his daughter Christina Engelbart, founded the Bootstrap Institute, which was later renamed the Doug Engelbart Institute in 1988, and began hosting seminars at Stanford University.

A Lasting Legacy

Despite his falling out with his lab and frustration with the differing directions, Engelbart received many accolades later in life. He was awarded more than 40 different awards, including the National Medal of Technology, the country’s highest technology award, in 2000. In 1997, he received the Lemelson-MIT Prize of $500,000, the largest single prize for invention and innovation in the world. He was also honored at the 40th anniversary celebration of the 1968 “Mother of All Demos” in 2008. Furthermore, in 2011, he was inducted into IEEE Intelligent System’s AI’s Hall of Fame and received the first honorary Doctor of Engineering and Technology degree from Yale University. In Engelbart’s later years, several books were published based on interviews with him and others from his lab.

Further Reading

- Learn more about Engelbart’s life and other inventions:

- Interested in other computer-related topics? Check out these COMSOL blog posts:

- The SpaceMouse, a redesign of the standard mouse used for CAD and COMSOL software

- Frances Spence, one of the first digital computer programmers

Macintosh is a trademark of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries and regions.

Comments (0)