Nobel Prize-winning chemist Hermann Staudinger developed a macromolecular theory that paved the way for the birth of polymer chemistry, which led to the production of plastics used in everyday consumer products. It took him almost two decades to convince fellow scientists to accept his theory. In celebration of his birthday, let’s dive into his life, discoveries, and legacy.

A Lifelong Scientist

Staudinger was born in Worms, Germany, on March 23, 1881. Little is known about his early life except for his interest in botany. (Ref. 1) His father, a philosophy professor and pacifist, influenced many of his views and encouraged him to study chemistry (Ref. 2). Staudinger earned the equivalent of a master’s degree at TH Darmstadt and then received a PhD in chemistry at the University of Halle in 1903. He then qualified as an academic lecturer under Johannes Thiele at the University of Strasbourg in 1907.

Later that year, Staudinger became a professor of organic chemistry at the Institute of Chemistry at the Technical University of Karlsruhe. Beginning in 1912, he spent 14 years as a lecturer at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zürich), where he researched polymers. In 1926, he became a Lecturer of Chemistry at the University of Freiburg, where he spent the rest of his career. The next year, he married his second wife, biologist and botanist Magda Woit Staudinger, and she became a coauthor on many publications.

A portrait of Hermann Staudinger taken in 1954 by the Nobel Foundation. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Early Discoveries

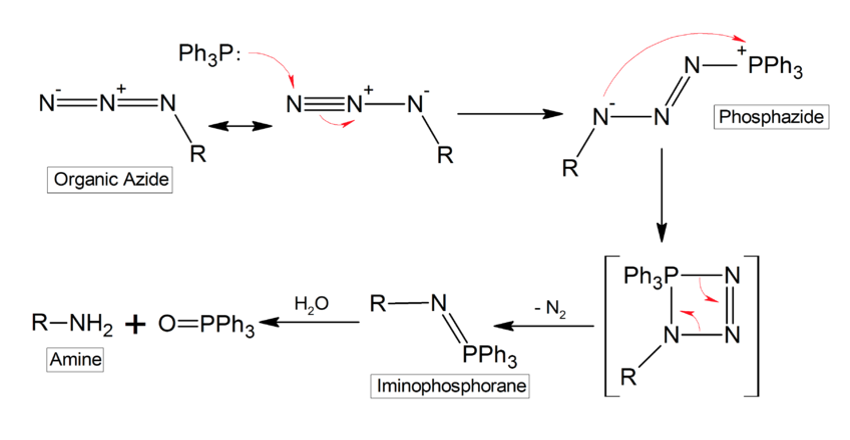

While at the University of Strasbourg in 1907, Staudinger discovered the family of organic compounds known as ketenes, highly reactive gases useful for synthesis of esters and amides. This discovery was fundamental to the future production of antibiotics such as penicillin and amoxicillin. Another early-career discovery came in 1919 when he and a colleague observed that organic azides react with triphenylphosphine (PPh3) to form a high yield of iminophosphorane (R3PNR’). This is now known as the Staudinger reaction (Ref. 3).

Reaction mechanism of the Staudinger reaction. Licensed for public use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0s via Wikimedia Commons.

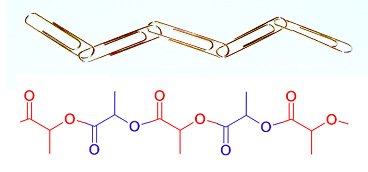

Staudinger dove into researching the chemistry of rubber while at his position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. In 1920, he published “Über Polymerisation”, a paper that rocked the international chemistry community. The paper was the first of a series in which he proposed a new theory — which he called “polymerization” — that materials such as natural rubber, starch, and proteins are made up of high-molecular-weight compounds formed by reactions that covalently bond many small, repeating molecules into long chains (Ref. 4). Staudinger called the resulting compounds “macromolecules”. The new theory contrasted starkly with the theory accepted at the time, which assumed that micelle-type aggregates like those formed by detergents were responsible for the properties of polymer materials.

A chain of paper clips as an analogy for a polymer comprised of small pieces linked together. Licensed in the public domain by Evastar via Wikimedia Commons.

Ahead of His Time

Despite Staudinger gathering evidence from hydrogenation, viscometry, and other experiments to support his theory, leading organic chemists were not easily convinced by it. It would take almost 20 years for the scientific community to agree with him.

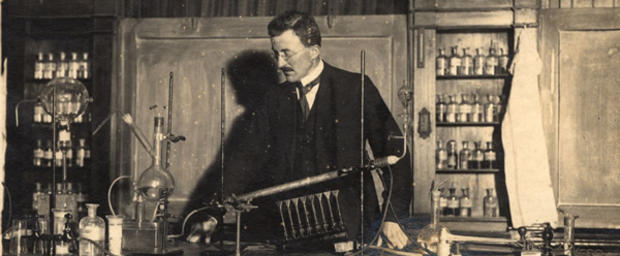

Hermann Staudinger conducting an experiment, 1916. Licensed in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1926, Staudinger partook in a debate that eventually became famous in the chemistry world. It took place at the meeting of German Natural Scientists and Physicians between advocates of the original aggregate theory of polymers and supporters of Staudinger’s new macromolecular theory. The debate was organized by chemist Fritz Haber, whom Staudinger had previously challenged over Haber’s role in gas warfare (Ref. 5). Staudinger had been very vocal about his anti-gas-warfare stance and suffered professionally for it.

At the debate, Herman Mark presented X-ray crystallographic evidence of the structures of natural polymers that suggested that macromolecules might exist, but a definitive conclusion could not be drawn. Several other chemists presented work that gave credence to Staudinger’s theory, but there was no consensus by the end of the debate.

Long-Awaited Recognition

Staudinger defended his theory for the entirety of his career, despite fellow scientists dissuading him and encouraging him to move on to work in other areas. Thought began to change in the 1930s when more research had been done on polymers, and his theory was slowly accepted by other chemists. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1953 for his discoveries in the field of macromolecular chemistry, over 30 years after publishing his landmark paper. Staudinger died in 1965, and in 1999 the American Chemical Society and the German Chemical Society honored his work as the foundation of polymer science by designating the Hermann Staudinger House as an International Historic Chemical Landmark.

Staudinger’s discoveries were fundamental in the birth of the field of polymer chemistry. His macromolecular theory applies to natural and synthetic polymers that have since been widely used in industrial materials for products that need light-but-durable structures, such as food packaging, circuit boards, spacecraft, and medical implants.

More on Polymer Science

Check out these blog posts on the science and simulation of polymers:

- A Novel Technique for Producing Ultrastrong 2D Polymers

- Analyzing the “Muscles” of a Robotic Manta Ray

- Modeling the Behavior of an Oldroyd-B Polymer

- Introduction to the Composite Materials Module

References

- “Hermann Staudinger,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Mar. 2025; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermann_Staudinger

- Science History Institute, “Hermann Staudinger,” 20 Mar. 2025;

https://www.sciencehistory.org/education/scientific-biographies/hermann-staudinger/ - “Staudinger reaction,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Mar. 2025; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Staudinger_reaction

- “Foundations of Polymer Science: Hermann Staudinger and Macromolecules,” American Chemical Society International Historic Chemical Landmarks, 20 Mar. 2025; https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/staudingerpolymerscience.html

- “Fritz Haber,” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 March 2024; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_Haber

Comments (0)